After Crashing His Air Force Jet the Pilot Walks Out of the Sierra Nevada...Hero or Traitor?

by Treas Manning

In the 1950s the cold war was escalating; the KGB had just been established and the Russians were gearing up to launch the Sputnik into orbit. Vietnam was split at the 17th parallel and McCarthy's witch hunt had raised the ardor to a fevered pitch.

America was engaged in a race of military mite and super power status came with a focus on state of the art aircraft with superior handling and missile firing accuracy. Readiness was paramount and Lockheed's T-33 was a front line training jet for advanced level Air Force pilots. Only a few trusted high level men were engaged in the secrecy of aircraft training, testing and development.

May 9th, 1957, one of those young top guns, 23 year old David Arthur Steeves, took off on a solo flight from Hamilton Air Force Base to Craig Air Force Base near Selma, California. The flight route took the young pilot over the Sierra Nevada near the rugged backcountry of Kings Canyon National Park. A routine flight plan was filed, nothing out of the ordinary except, the young pilot and his top level aircraft disappeared from radar and never landed at the central valley Air Force base. A search and rescue mission was launched but failed to find any trace of the pilot or his airplane. First Lieutenant Steeves was declared dead and a death certificate was mailed to his family.

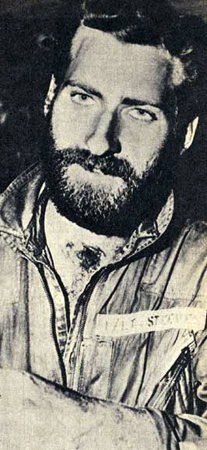

Fifty-four days after his disappearance, a full bearded, battered and half starved man in an Air Force flight suit aimlessly limped into a hiker's camp. He gave his name as Lieutenant Steeves and told his story of survival.

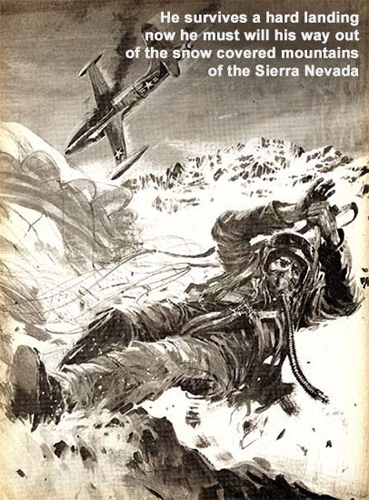

A violent explosion in the cockpit had left him unconscious and his jet spiraling out of control. He slowly regains consciousness and instinctively fought to control the spin. The aircraft leveled out but was filling with smoke, he is forced to eject and deploy his parachute, dropping into the most mountainous backcountry of the Sierra Nevada. Taking a hard landing, both ankles are badly sprained and he finds himself wearing only a light weight summer flight suit.

He had gone two weeks without food, wandering, trying to navigate his way out of the mountains. About to cede to his dismal situation he comes across a ranger's cabin finding cans of ham and beans, fish hooks, and line. His hope of survival is renewed and he continues his tramp out of the mountains. In May the high country of the Sierra, with elevations well over 11,000 feet, is still covered with snow; rivers and streams are often a torrent and dangerous to cross.

The 23 year old was at first greeted as a hero, his struggle was seemingly impossible to persevere. The Saturday Evening Post offered Steeves $10,000 for an exclusive cover story of his ordeal.

Air Force superiors took his testimony and laid out a search for his aircraft. Months of searching and reviewing his story came up empty, not a piece of the wreckage of the top level aircraft was found. Rumors and suspicion were mounting; how did he survive without food for two weeks, let alone find the strength to continue walking and stumble onto a cabin with stores of food. Fifty-four days and he manages to climb his way to safety, with no trace of the crash sight? Lieutenant David Steeves' heroic story seemed unlikely. The magazine pulled back on their offer claiming discrepancies in his story, their accusations were never spelled out.

A more plausible story was being piece together by the Air Force. A traitorous pilot, flies his military jet deep into Mexico, hands it over to the Russians for payment into a foreign bank account. He is then flown back over the Sierra Nevada and dropped into the mountains. Food was planted at the ranger's cabin along with a preplanned route back to civilization. A weary pilot would then tell his well rehearsed story and no one would be the wiser.

With lack of hard evidence formal charges were never filed but rumors and suspicion would plague his military career until 1st Lieutenant David Steeves would ask his superiors for a full discharge from the Air Force. Steeves' civilian life brought divorce and the loss of custody of his young daughter, he lost the support of most of his friends. He managed to find work as a commercial pilot and was involved in designing parachute planes. Driven by the cloud of conspiracy hanging over his head he would spend the rest of his life combing the Sierra from a rented plane hoping that the discovery of the wreckage would clear his name.

In 1965, civilian David Steeves, would die in a plane crash. Twelve years later a group of Boy Scouts while backpacking in Kings Canyon would discover a large piece of cockpit from an Air Force jet in a shallow alpine lake. The serial number was clearly present and matched with 1st Lieutenant Steeves' missing Lockheed T-33.

for more info please go to "Taylors aviation archaeology" on face book,

be safe and good luck with your adventures.